Prize-winning poet, acclaimed novelist, editor and playwright, Jeff Phelps, is the author of two novels Painter Man (2005) and Box of Tricks (2009), both published by Tindal Street Press and the poetry pamphlet Wolverhampton Madonna (2016) published by Offa’s Press. He is a founding member of Bridgnorth Writers’ Group and was recently a ‘poet on loan’ in West Midland libraries. He is married with two grown up children and now lives in Wiltshire. His website is www.jeffphelps.co.uk

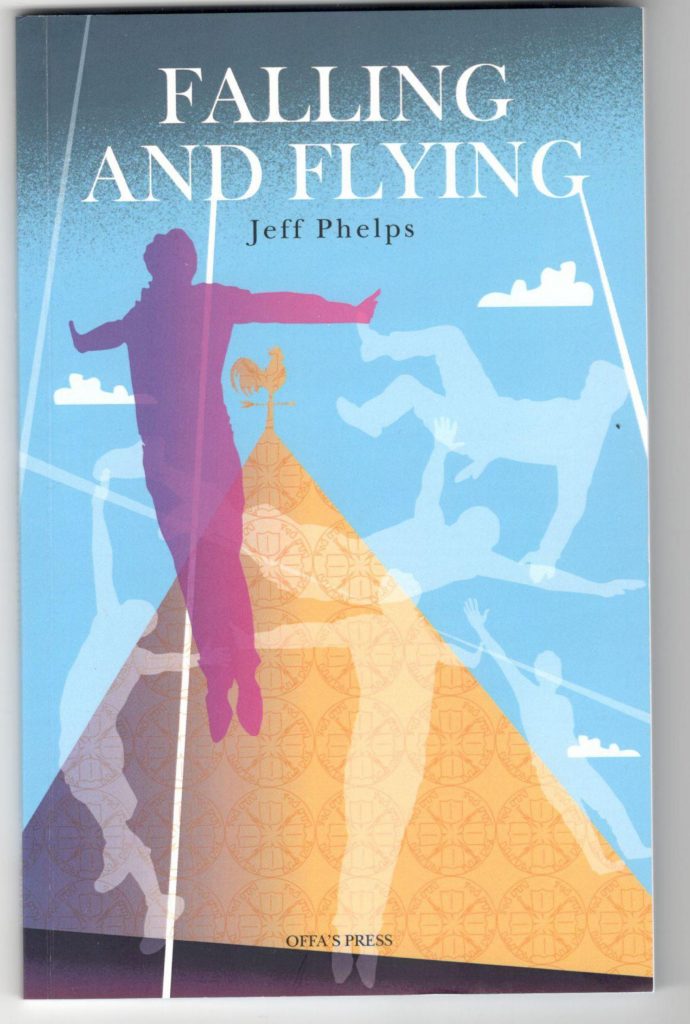

Falling and Flying is an impressive first full-length collection of poems. The presentation and running order of the 57 poems contained in this volume is well thought out. The falling poems and the flying poems provide a strong opening followed by a series of poems that cover subjects at ground level and beneath the ground. Further in, there are groupings of poems about the moon, birds, saints and churches, memories from childhood, current affairs, music and art.

The collection opens with two powerful poems titled ‘Cadman’s Leap’ and ‘Cadman’s Wife’ which narrate the tragic early death of an 18th century showman and rope slider from Shrewsbury and the subsequent loss felt by his wife. The second of these poems achieves through rhyme and repetition a sense of sustained lyricism in its poignancy.

In ‘An Avebury Stone’ the distant past struggles to come alive where ‘one frozen circle dancer / [is] waiting for the music to begin’ and in ‘Devizes White Horse’ the animal that may have once ‘cantered across this sweet meadow / of orchids’ is now ‘a stranger to itself’. A preoccupation with the more recent past is evidenced in ‘The Lost Village of Imber’, an uninhabited village that forms part of the British Army’s training grounds on Salisbury Plain where the entire civilian population was evicted in 1943 to provide an exercise area for American troops preparing for the invasion of Europe during the Second World War. To this day, the village remains under the control of the Ministry of Defence.

Staying on the subject of war and the ravages of war, ‘On the Bommy’, Phelps’ concluding stanza makes us think about some of the bigger consequences of history turning a poem about a children’s playground among bombed-out buildings into a more powerful statement about the futility and cost of war:

Damage brings forth damage in its turn.

Each generation pays the next with interest.

We plundered that barren patch with no concern

for that family so cruelly dispossessed.

One of my favourite poems in this collection is titled ‘Waterway’. Its subject matter, an old canal, is only hinted at and not named. The details are sketchy and the location not given. A lot is left up to the imagination and the disconnection between what might have been there then and what is there now is handled well:

Now I haul myself up

expecting water or a towpath

and find only derelict gardens,

no sense of direction.

For all its evasiveness, it is a poem full of atmosphere and mystery.

Other poems range widely in both subject matter and location: a visit to an eye hospital, bicycles outside Oxford station ‘ranks of them waiting, flashing / in the sun like Wordsworth’s daffs’, dowsing with a ‘Y-shaped hazel, alder or goat-willow’, poems in praise of the moon, an ekphrastic poem based on an oil painting by Joseph Wright of Derby and a poem about Cornish saints. Some pieces are light-hearted, such as ‘Gerald the Ginger Cat’ and ‘An Idiot’s Guide to Freedom’ while others are more serious such as ‘I have been a stranger’ and ‘Yes I have wished.’

Several poems make reference to music, in particular, the ‘Psalm for Musicians’ and the ‘Schubert Variations’. This is not surprising given that Phelps’ son is a classically trained musician. The prose poem ‘Schubert Variations’ is a very fine piece of writing.

Here is the opening section:

When I heard the sound of coal tumbling into the cellar under my window I imagined black notes falling from a piano in a cascade of sharps and flats. The streets were full of horses pulling coal carts, heading to the country where there were operas in huge palaces. And that was how I came to run after them, pulling up my borrowed breeches, my spectacles thumbed and greasy.

Even here, attention is paid to form. Each of the six paragraphs begins with the phrase ‘When I heard the sound of…’ It might be a knock on the door, someone’s voice, a piano or the ‘symphony in [his] head’. As a composer, every sound is important to Schubert and it carries with it its own connotations. What is more, all these sounds are already present or hinted at in the first paragraph. Each one of them is expanded upon and explored in its own right in a poetic equivalent of a set of variations on a stated theme.

Stylistically, the collection covers a variety of forms including sonnets, tercets, a prose poem and visual poems. The circular ‘Heartwood’ poem, reminiscent of tree rings, is a dendrochronologist’s dream because the exposed stump of the tree does all the talking. A number of poems follow strict rhyme schemes which are well executed. Helpful footnotes are provided where appropriate.

This is a wide-ranging collection that takes us through a good deal of history while at the same time raising questions about some of the more pressing issues of our own time. Highly recommended.