He put his hand over mine and it looked so old. “No one will even want them,” I said,

“They’re dated”. He said that wasn’t the point and walked over to the white dresser by your bed.

“Let’s start with her shirts,” he said, and I told him your shirts were in the tall dresser by the window. He put a shaky hand on your bed for support, and I could hear his knees creak as he stood. The last time we were in your room together he could have carried your dresser over his shoulder.

“The top drawer?” he asked.

“No,” I said, “the third down.”

He opened the drawer and pulled out a neat pile of tiny shirts that were so colourful. When he took the shirts out of your drawer, the room changed. It wasn’t how it was the last time you were in it, and so it wasn’t really yours anymore. I started crying, and he came over to me with your shirts and sat down. He said, “We knew this wasn’t going to be easy, Elle, but you’re doing a great job.”

The shirt at the top of the pile was yellow with a little smiling duck on the front. I thought, if only this duck knew—everything in your room seemed so unexpectant of tragedy.

I could see your dad looking at me out of the corner of my eye. He had that same look when he found me with the pills in your closet. He put his hand on my shoulder and said, “Elle, she’s not here.” He took your shirt from me and went to put it in a black garbage bag.

“No, Christ, no,” I said, “I brought boxes, they’re downstairs.” I went to stand up, but he offered to get them. He left the room and I listened for his footsteps to reach the bottom of the stairs. I stood up and walked to the door and locked it.

On your bedside table there was a framed picture of us. I picked it up and saw from the dust that it had been moved. I heard him coming back upstairs, and then I heard him gently trying at the door handle. “Elle,” he said from behind the door, “come on, let me in.”

“So,” I said, “you have been in here.” He didn’t say anything at first, and I waited for him to deny it, but then he said,

“Once, when I was drunk, but I didn’t take anything.” Then he said, “Elle, you told me I could keep the house if I promised to keep the room just as it was, and I did, I have.”

I knew he was telling the truth because the rest of the house had gone to shambles. There were cracks up the walls, the wood floors were black and warped, a musty smell was coming up through the vents; the whole house was falling apart except for your room. This room was the same, even structurally, like the house was helping to keep his promise too.

I picked up the picture and looked at us. “Hi, sweetheart,” I said to you, “beautiful, beautiful little sweetheart. I never stopped thinking about you for one second,” I said. “I just couldn’t come back here, you know? But I never forgot, no ma’am, and when your dad said that I had moved on, baby, that wasn’t true. I didn’t move on, I just kinda’ kept on surviving. I met another man, I did, and it wasn’t your daddy, I know, but your daddy wasn’t the same after, baby. And this new man, he was as nice a man, as nice as they come. And he gave me your sisters, and all growing up they asked about their big sister, and all growing up I told them about you. Well, they’re a lot older than you are now, and have babies of their own, but you’re always their big sister watching over them, protecting them, I know”.

I put the picture back down. I heard him from behind the door again.

“Elle,” he said.

“Just one more minute,” I said.

The sun was coming through the window, which was strange, you know, because whenever I pictured your room, it was shrouded in gloom. But that’s not how it was, not with that eastern-facing window. The room was bright and laughing, and I remembered how I chose the colours for just that reason.

I opened your door to let him back in. His eyes were red and he kind of shrank away from me. “I’m sorry,” I said.

“Don’t worry about it,” he said. He had the boxes folded flat under his arm and said, “It took me a while to find these, flat boxes.” He smiled a little, that crooked smile that you both have. He put the boxes down in the centre of the room and started putting them together. “All to Goodwill?” He asked.

“No,” I said, “but I’m going to mark each of them.” I was staring at the door frame where we had marked your height. I followed the notches inch by inch, and when they stopped at three and a half feet, my eyes kept climbing.

“Okay,” he said, “they’re ready”. He pulled one of the boxes next to the pile of shirts and sat back down. I joined him on the floor, and he said, “So, how far away is Tessa and…” He tried to remember my son in-law’s name. I told him that I didn’t want to talk about anything else outside of your room. He nodded and reached for your shirts, but I stopped him. “Elle,” he said. And I said,

“Can you put them back just how they were? Just for a second, then I promise we will pack everything up.” He nodded and got up and then I said, “Sit down with me after.”

He put your shirts back where they were and stepped away from the dresser. He grunted a little as he squatted down next to me. I took his hand in mine and held it. And the two of us sat there, for a while, in your unchanged room.

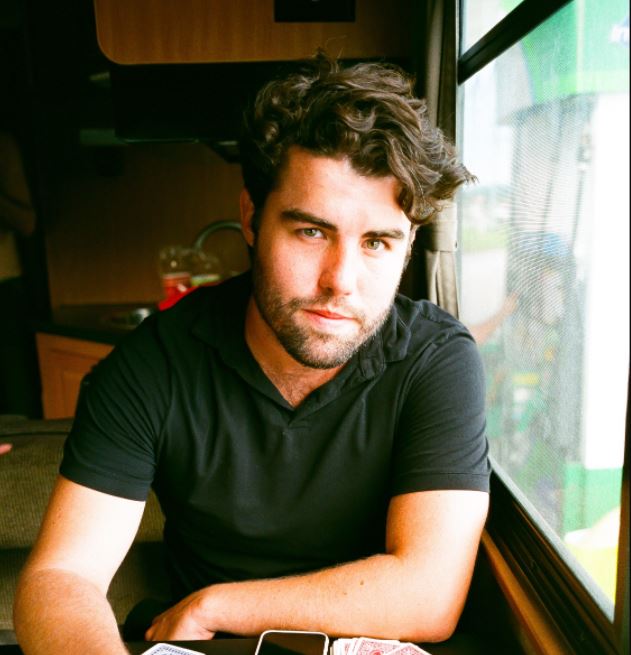

Sean Cahill-Lemme was born in Park Ridge, Illinois—yes, he does consider that to be Chicagoland—to a family of raconteurs, the Northside descendants of Erin. He has no problem admitting he’s not the best storyteller in his family (you wouldn’t either if you ever shared a pint with his gramps), but he does believe storytelling can be more than just entertainment after the real work is done.

He has always been hesitant to share his stories, but encouragement from an incredible culture of Chicago writers has convinced him otherwise.

When it comes to writing, Sean puts truth above all else—if readers walk away feeling something real, he will have done his job. Beyond that, he hopes that readers enjoy his stories as much as he has enjoyed writing them.