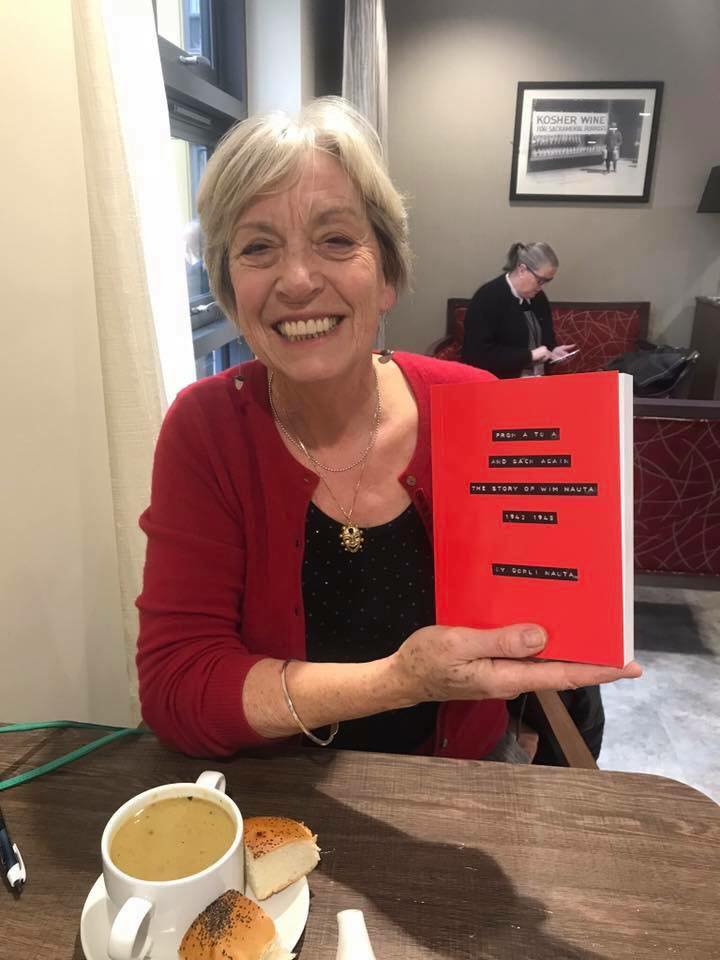

You have recently written and published your book From A to A and Back Again which is based on your father’s experience of forced labour in Auschwitz 1943-5, and his letters home to Amsterdam. How fascinating. Congratulations, Dorli. Could you tell us more about it?

The first time I found out that my father, Wim Nauta, had been in Auschwitz during the Second World War, was when he told me that he was applying to the German Forced Labour Compensation Programme.

In 1942 The German State began to suffer setbacks; the advance of the army was halted, and the troops stalled at many fronts. More and more German men were sent to the front, more and more German women had to work in the war industry. There was a severe shortage of labour and the Germans started to look elsewhere for workers. The Netherlands had to supply labour also. In June 1943 there was a call up announcement for all males between the ages of 18 and 20 to report for work in Germany. When my father and his friends returned home from a rambling weekend away in the countryside, their call up papers were waiting, informing them to report to the Labour Exchange the next Thursday.

About 550k Dutch people were forced to work for the Germans. That represented, with regards to the number of inhabitants of 9 million, more than 6%. The Netherlands were hit hard. A total of some 30k people died of the consequences of this forced labour.

But Wim Nauta came back to Amsterdam, hence the title From A to A and Back Again.

In translating the memoirs, how did you try to get your father’s voice across?

I made several attempts at translating the letters. I was trying at first to keep very true to his voice, with the slang and upbeat tone of the letters. But it didn’t make for the best English, as my daughter Jessica pointed out!

After a few tries I became more relaxed about wanting to translate ad verbatim, and I concentrated more on getting the meaning across in good English.

With so much information to work on, with letters, diaries and memoirs, how did you begin to organise the structure of your book? It must have needed a lot of patience?

On the 27th January 2013, Holocaust Memorial Day, I met Chava Erlanger at the Imperial War Museum North, where she unveiled her artwork; ceramic stars representing the Star of David.

We got into conversation about the mutual connection we both have with Amsterdam. We became Facebook friends and stayed in touch that way.

When writing the book I tried to fit everything in chronologically, with links in my own voice. I found it hard to make a selection out of all the material that I had, especially all the old historical documents. I tried several ways, but nothing was ever quite right.

In May 2015 I made a version which was printed and passed around family and friends.

You have included colour reproductions of original photographs in your book with co-designer Gwen Riley Jones, a freelance photographer who works at the John Rylands Library in Manchester. What are some of the images you included, and are any images of the letters included?

Around that time I met up again with Chava in the John Rylands Library, she introduced me to the photographer Gwen Riley Jones. This time I was able to give her a version of the book, which had as working title The Ticket.

Then Chava got in touch with me and said this story needed to be published. She approached the Six Point Foundation, a charity for Holocaust survivors; they agreed to sponsor me. Gwen Riley Jones, photographer and publisher came to help me. Gwen and I worked together, editing, designing and re-editing. At last on 1st of December 2017 the book was published.

The book starts with images of my father’s photo album, followed by all the letters in Dutch on one side of the page, with the translation in English on the opposite page.

There are also images of wartime documents, notably a train ticket and a Red Cross Telegram and family photographs.

Your father was called to Germany with two of his friends. They were all musicians. Which instruments did they play, and what kind of music? How much insight did you get into all three characters through your father’s memoirs?

My father and his friends played several musical instruments; guitar, accordion and mandolin. In the photograph album A/Z Oberschlesien you can clearly see the instruments slung over their backs. The music they played were popular songs of the time such as Drei Vagabunden, which they played on stage as part of the Dutch Cabaret performance. The show was called Seltene Witzen (Silly Jokes).

I have a collection of the music they played in a folder that my father gave me. It is quite a mix amongst others: Stardust by Duke Ellington, Bye Bye Blues, Samoa Eiland, Polish folksongs, Oh Suzanna, Do You Remember The Night In Zakopane, Bing Crosby’s Cowboys’s Medley, You Are My Lucky Star, Caravan, Pagan Love Song, Poor Nelly Gray and many more in German, English, Polish and Dutch.

I don’t think I ever met the two friends Jan and Carel, but reading the letters gives you some idea of what they were like. My grandmother mentions that Wim was very lucky that his friends came with him.

Could you please share with us an extract from your book?

Extract from a letter from Wim to his family in Amsterdam:

Auschwitz, 2nd November ‘43

Dear All,

I have just received your letter dated Sunday 17th October, so that didn’t take that long to arrive; only a fortnight. You wrote that you had sent a parcel two days previously, well that was so, because yesterday I got a card to say that I could collect a parcel in Kattowitz. At five o’clock I jumped on my bike and was off, then onto the quarter to six train and at half past seven I arrived in Katto and quickly went to the Express department to collect it. Fortunately everything went really quickly and the parcel was completely in one piece and everything you wrote about was in it. It’s fantastic and of course I thank you very much. Then I had something to eat and back on the nine o’clock train.

I arrived back in Auschwitz at half past ten at night. I went to the bike shed and started pedalling so as to be back quickly. I was about halfway, when passing the bus stop I saw a girl of about twenty five years old. She asked me if there were still any buses going. Well of course there weren’t any buses anymore; she had two suitcases with her and was on her way to the station. I decided to do the gallant thing and put the suitcases on my back and together we went to the station. On the way she told me that she came from Vienna and that her husband had been stabbed to death in a street fight, during the revolution. So she was from the right side, and according to her, almost all Viennese are. When you go into a shop there to buy something, you wouldn’t dream of giving the Hitler salute, not like here, because there you wouldn’t get served. According to her, Vienna is still the way it was before the war. At half past eleven we arrived at the station and we said our goodbyes. She gave me three apples, a handful of cigarettes (eight!) and 5M. Of course she also asked me to write to her sometime. Great wasn’t it? The only thing was I didn’t get back until half past twelve, but that did not matter.

As regards moving on Moe, that’s nothing you know, we would like to, but you can’t leave here at I.G.Farben.

As forced labour my father and friends were allowed to travel on specific times and days within a 100 km radius.

Another extract taken from the memoirs my father wrote; I paraphrase, it concerns the immediate aftermath of the night of 13th February 1945 in Dresden:

After 5 am there was no ‘all clear’ siren. The electricity had been cut. They waited until they heard no more bombs drop, then they went outside.

The first thing Wim saw was a dead horse lying on the pavement. The house next door was on fire. The inhabitants were taking their furniture outside and Wim and his friends helped them to get it all out. They debated what to do next. It was clear that they had to leave Dresden as fast as possible. They made their way towards the Elbe. Dresden was a big, smoking rubbish heap. The anti-aircraft gang had made little paths where possible, between the debris. Along these paths they arrived at the river, but they didn’t know what was safer; to stay on this side or to go over the bridge, which miraculously had hardly been damaged. They decided to cross the river. At the other side they walked down the steps, to get to the sandy riverbank. Under the arches they saw an unbelievable amount of dead bodies; people who had lost their lives during the bombardments. When Wim saw this he became very frightened and realised that it would only need a bomb fragment or a splinter of the anti-aircraft fire, for him to end up amongst these victims.

They were walking along the river’s edge, when they heard the buzzing of aircraft up high. From the bombardments on Auschwitz, Wim had heard about the theory that a second bomb never falls in the same place. So if you were too late for a shelter, you had to jump into a bomb crater, stand to the side and hope for the best. The three friends put this theory into practice and ran from crater to crater.

Where is the best place to get a copy of From A to A and Back Again?

My publishers are a small company and I am my own agent. To get a copy of my book you can send a cheque for £16.99 plus postage of £2.90 together with your address to:

Dorli Nauta, 16 Eaton Road, Bowdon Altrincham WA14 3EH Cheshire UK.

I also have a Facebook Page and you can message me on there, or on Messenger.

Have you any future plans for further books, or projects?

I haven’t used all the material and documents I have in my possession, so I might write a kind of ‘follow up’ to this book. I also write and tell stories for children; so far for my grandchildren but I have plans to publish a small collection sometime.