Can you tell us about your collection, Grenade Genie?

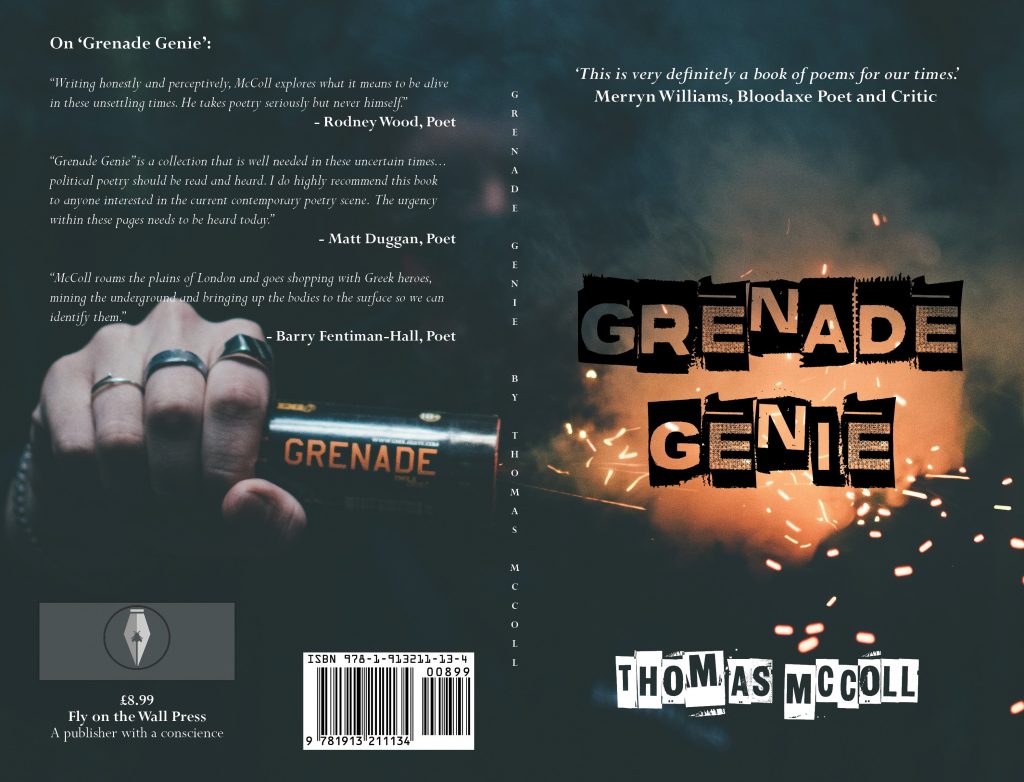

Grenade Genie, published by Fly on the Wall Press, is very much a book for people who want to read poetry that engages with, and says something about, the world in which we live. The book is split into four sections: ‘Cursed’, ‘Coerced’, ‘Combative’, and ‘Corrupted’, and within those four sections are poems which are all very much rooted in real-life, albeit with often fantastical elements. Inside these pages you’ll find, for instance, two-headed doctors, fashion-victim gorgons, a literal library, commas that kill, a little-known terrorist group called The Pedestrian Liberation Organisation, and grenade-encased genius.

It’s a book that has a lot of variety in terms of subject matter, but with one main theme that runs through the whole of the book – namely that, ultimately, everyone and everything is expendable, and while this knowledge can generate either a sense of hopelessness or the nothing-to-lose strength to rail against it, one strength of poetry is that, even if only the former gets expressed, the latter is automatically achieved, and in a very concise way too, making it all the more effective, and the main reason really why I’ve chosen this form to write in.

I enjoyed reading many poems in the collection, I found ‘Security Pass’ and ‘Jackpot’ particularly relatable. Do you have a favourite poem in the collection?

Thank you. I’d say the title poem, ‘Grenade Genie’, is currently my favourite. It’s about someone possessing genius and wanting to use it to change the world but, finding that it’s encased in a live grenade and requiring the spark, has little choice but to pull the pin in order to release the genie inside that will grant his wish, except that, of course, the explosion kills him, and his atoms (which form into lesser versions of himself) then proceed to get all of the credit instead of him. However, by pulling the pin, this person wipes out the establishment that was blocking all progress – an establishment of atoms from a previous explosion – and so it goes on (as it always has and always will).

‘The Phoney War’ was another poem which stayed with me after I’d read it. Can you share where the inspiration for this poem came from?

Thank you again, not least because the ‘The Phoney War’ is another personal favourite of mine in this collection. It’s ostensibly a simple poem about two young children – two brothers – in the 1970s, in their living room, playing at being World War Two Tommies fighting the Jerries, but it’s the ending that gives the poem its resonance, and it took a long time, and many drafts, for me to get that ending right.

I seem to have managed it, though, as various reviews of the book have described the poem’s ending as ‘devastating’ and ‘heart-wrenching’, which was very much the effect I wanted to achieve, especially as it’s based on a true event, so the ending isn’t just a device, it’s something real, something that was really felt by the person who was affected, the grandmother there at the kitchen stove who, unlike the boys (with their ‘umbrellas for rifles’, ‘smoking pencils, feeling tough’), had actually lived through the war and experienced, first hand, how terrible it was.

Whenever I’m introducing this poem at events, I say it’s a ‘poem about childhood, and play, and when reality intrudes on play’. And though the poem represents me as a child, it also represents me now, as a middle-aged adult who’s come to understand, much more, the significance of how harmless fun for me in the past wasn’t always such harmless fun for others.

Do you have a set writing routine? How long does it take you to write a poem?

I don’t have a set writing routine as such – it’s simply writing as and when I can – but I’ll seize any opportunity there is, and always find some way of making time for it, for all I know is, if too much time goes by without me being able to get my fix in some kind of way, I’ll soon become quite grouchy.

As for writing an actual poem, the length of time it can take has, in the past, ranged anywhere from a day to upwards of 25 years! But that’s the thing, while the writing of an actual poem can be quick, the editing of it (and then re-editing of it over, over and over again) can end up taking almost forever. For instance, a poem that’s in the book, called ‘Statement by the Pedestrian Liberation Organisation’, was first published on the letters page of the Islington Gazette in December 1994 as a very short 8-line poem; then, in July 1996, it was published as a 17-line poem in DirectAxiom, an anthology put out by the direct-action pedestrian rights group, Reclaim the Streets; then, by the time it was used for a film-poem I did in March 2010, it’d expanded into a 45-line poem; then, finally, in November 2017, it was published as a radically altered 54-line poem in the online magazine, ‘i am not a silent poet’ (which, apart from a few further tweaks, is the version which appears in the book).

What are you reading at the moment?

I’ve taken to reading writers’ biographies lately, and at the moment I’m reading Jubilee Hitchhiker – the life and times of Richard Brautigan, by William Hjortsberg. I discovered Brautigan’s writing relatively recently, starting with one of his novels, Sombrero Fallout. I’d been thinking, for quite a while, that I needed to try some Brautigan, and one day when I was in the Waterloo station branch of Foyles, I decided to do just that, and picking Sombrero Fallout from the three or four books of Brautigan’s there on the shelf, I read the foreword by Jarvis Cocker that really sold it to me, and I’m glad he did as, on buying the book and reading it, I found it really was every bit as good as billed – quirky and wise, instant and profound, and about nothing and everything, all at the same time.

Do you have any books or poems you’d like to recommend to us?

The last books I read are all ones I’m able to recommend – all pamphlets, as it happens: Rodney Wood’s When Listening Isn’t Enough, Julie Stevens’ Quicksand, and Damien Donnelly’s Eat the Storms, all quite different from each other, but all three of them quality reads. I also recently read a pre-publication version of Darren J Beaney’s The Machinery of Life, and it’s now been published, complete with my written endorsement, so it’s already very much on record that I’m recommending that one!

Has the pandemic / being in lockdown impacted on your creative process at all?

It hasn’t in terms of actual writing, but it has in terms of me being able to promote my work, and I felt the impact keenly right from the off, with Grenade Genie being published pretty much just as lockdown began, in April 2020. I’d been all set to go on what would have been my first ever proper tour, having organised feature slots at various live events and festivals in London and further afield – including a 60-minute solo show at the Leamington Poetry Festival in July, and shorter headlining slots in Coventry, Birmingham, Rochester and Saltburn – but then, just as pre-orders for the book began to be taken, the first lockdown began, and slowly but surely all the dates I’d organised got cancelled.

However, I was immediately positioned to get straight into the swing of the ‘new normal’, for the organisers of Winchester Fest, who’d booked me for a live in-person event to be held on 18th April, the day after my book was published, decided to go ahead anyway with the event, but online, and so facilitated the launch of my book via Zoom with a 60-minute feature – and, with events now only able to go ahead if they went online, opportunities began to arise which otherwise wouldn’t have happened. For instance, I ended up being a featured poet in the Bridgewater International Poetry Festival, based in Virginia, USA, a festival which I’d normally have had to travel to in order to participate but now could be a part of from the comfort of my home in London. And new opportunities arose regarding radio as well: Shows which, previously, I’d have had to travel to in order to talk in the studio, I was able, now, to be a part of without leaving London and, in this way, I ended up being on Rick Sander’s ‘Brum Radio Poets’ show on Brum Radio, and also on Hannah Kate’s ‘On the Bookshelf’ show on North Manchester FM, and I managed too to get poems from the book featured on BBC Radio Kent and BBC Radio West Midlands. So, while there have undoubtedly been some disastrous elements to lockdown, I’ve found, too, that it’s been, to some degree, a case of ‘what one hand taketh away the other giveth’.

What are you working on at the moment? Can you share details of any other projects you’re working on?

I’ve written both a novel and novella, and while neither of these manuscripts have found publishers yet, extracts from them have been published as standalone stories in magazines such as The Ghastling, Sick Lit and Here Comes Everyone. Other short stories of mine have been published in magazines such as Bare Fiction, Smoke: A London Peculiar and Fictive Dream, and some of these short stories, collected into a manuscript, were longlisted in the Mslexia First Drafts Competition in 2017.

Your writing encompasses many different themes. How do you decide whether to develop an idea into poetry or fiction?

Well, I’ve always written prose in tandem with poetry, and while it might be my downfall that I’ve never solely concentrated on one form or the other, one good thing is that there’s been much cross-pollination, with poems morphing into both flash fiction pieces and short stories, and vice versa. For instance, the first poem in the ‘Combative’ section of my book, entitled ‘Shopping with Perseus’, started out as a piece of prose, a 721-word story that was first published in the urban feminist literary magazine, Geeked; then, after being edited down to 500 words, it won first prize in the Third Annual Stories of SW1 Writing Competition; then, finally, after being edited a little more, was changed into being the poem that’s in the book.

Is there anything else you’d like to add?

Not really – as I think a lot of things were covered there in the above questions – except to say that my book, Grenade Genie, is available from my publisher, Fly on the Wall Press (and direct from me if you’d like a signed copy). Cheers!

Review of Grenade Genie by Kev Milsom

It’s always great to have an interesting quote at the beginning of any book review; something that gives a teasing indication of what is to come, like an intriguing starter on the menu of a new restaurant, yet to be explored.

In this case, the quote is indeed intriguing and succeeds in pulling us in for further exploration: ‘25 brief studies of the cursed, coerced, combative and corrupted’.

Thomas McColl has completed a collection of poetry, published by Fly On The Wall Press, who are certainly not unknown to us here at Ink Pantry, as we have also interviewed Isabelle Kenyon, Elizabeth Horan and Colin Dardis from the same publishers.

Thomas has a fine pedigree in writing, collaborating with Confluence Magazine, The High Window, Never Imitate, and Write Out Loud. He has also performed poems from the book on BBC Radio Kent, BBC Radio WM, Brum Radio and London Soho Radio.

So, let’s peek into Grenade Genie and see what lurks within. We start with the ‘Cursed’ section, which contains seven poems. The first of these is ‘No Longer Quite So Sure’. This poem is very strong on visual imagery and it’s easy for the reader to sit back and relax into the words being relayed to the mind. Alongside the creative, descriptive vocabulary, here’s a message here; namely one of social observation and relevance. Metaphors fly around and each of them is related in a way that the reader can quickly interpret and identify with. In this way, a simple bus ride is cleverly morphed into likening buses to bison and citizens become grass.

‘The council is yet to cut back

the branches of the trees on Newman Road,

which means that, halfway through

my journey to work on the bus –

and always just as I fall asleep

in my usual seat on the upper deck,

with my hooded head at rest against the glass –’

Strong, underlying messages within Thomas’s words continue with ‘The Evil Eye’, a poem about damaging addictions to technology and different forms of online manipulation.

You’ve allowed yourself to get caught in a cobweb

spun by a social spider that sucks you dry of information,

then leaves your hollowed-out exoskeletal frame

to rot on its website.’

Thomas uses the opening ‘Cursed’ section of the book to comment upon such powerful subjects as refugees, government cover ups and more.

Keen to explore what lay within the second ‘Coerced’ section, I read ‘Security Pass’, a highly personal exploration of how our identities become less personal and individualistic within a large company, or business – perhaps the author relating to his current job within the House of Commons, or perhaps his former career within a famous, High Street bank.

‘I’ve just been made permanent –

yet already I know I’m completely expendable’.

The writing style which Thomas employs is very effective. You can ‘hear’ his voice within the poems and it’s clear that his passion for social commentary is expressed very well. While the topics are clearly very personal, the expression of his thoughts are relayed in a way that the reader can easily relate to. Thus, we share Thomas’s journey, rather than be admonished, or feel threatened, by it.

Fine, flowing examples of Thomas’s social commentary occur throughout this poetry collection and, I found that at every turn, I was intrigued by what he had to say – again, largely down to the way in which he writes and how he expresses his personal thoughts and observations so well.

In ‘Jackpot’, Thomas asks us to join him on the platform at London’s busy Oxford Circus underground station, likening the rush to get on a train to being in some form of human lottery.

‘Here I am at Oxford Circus station once again,

allowing myself to be part of the human jackpot

that’s released each time a train pulls in.

I don’t know if anyone else ever thinks this,

but whenever I’m on a train that’s entering this station

and I’m watching the branded posters on the platform wall

whiz past my carriage window,

I’m reminded of playing a slot machine.

OK, this one has a single horizontal spinning drum instead of the usual vertical three –

but it’s not like the odds are stacked

any more in my favour.’

We’re even welcomed into joining Thomas, back in the heady days of the late 1980s as he goes out on the town in Birmingham in his twenties. It’s clear he hates his bank job and wants some release from the pressures of working life (who hasn’t been precisely there?) that he describes so eloquently (and realistically) in his poem, ‘Nightclubbing In Brum, 1988’.

‘I look a right sight

as I’m travelling into Brum on a Saturday night.

It’s hard enough making the grade

when still a hapless teen at the tail end of Thatcher’s decade,

and though one plus

about these times is that I’m able, still, to smoke a fag

while swigging a can of beer

on the top deck of the bus…’

‘Last week, I tore my trousers and lost a button,

and being as I work for Lloyds Bank in Sutton

(high standards in that posh part of town),

I don’t want yet another dressing down,

for it’s 1988,

and though everyone says how much they hate

being made to wear a suit

(that’s more often than not a Mr Byrite one to boot),

I at least get value out of mine,

but some consolation! – Roll on 1989’…

In short, Grenade Genie is a fine collection of stylised, creative poetry, expressed in literary terms that anyone can understand. Highly recommended.