new year’s eve

Sometime before midnight, he walks out onto a balcony. He climbs onto the ledge and stands there — on the tails of an old year, inching precariously toward the new. He spots me below, on the other side of the street. He stops. It has been raining all night. The road holds reflections of the city skyline on the ground, like a dazzling kaleidoscopic painting on a wet canvas. Water drips into the drains, reflecting lights like electric fire. He climbs off the ledge; his eyes remain fixed on me. He smiles but looks embarrassed. Across the road from me, he is two floors up from a tree-lined boulevard. He disappears back into his apartment. I return my attention to the street again. Most of the snow has melted during the day, and now a glossy sheen covers the roads. A small group of revellers come into view, giggling and swigging drinks. They kick and throw what’s left of the snow at one another. Later on it becomes busy. People are rushing hither-thither, I guess from one party to another, before the midnight hour strikes. He has returned to the balcony, now brandishing a flute of champagne in his hand. As the clock strikes midnight, I hear cheering from the cafes and bars. He raises his glass to me and mouths “Happy New Year”. Somewhere fireworks go off. I watch their dazzling colours reflect in the apartment windows in front of me. I scan from window to window, stealing delight from celebrations never intended for me. He remains out in the cold for another hour or so before waving goodbye and returning to his apartment.

spring

Life has returned. People on the street look fresh and rested from their winter hibernation. It’s as if they too are sprouting the first shoots of optimism for what the year has in store.

One hazy morning I am forced forward with a violent strike. I’m stripped—my clothes torn away with impatient hands. An overweight woman huffs and puffs as she picks up my scattered clothes from the floor. She leaves. I’m left naked. A few people in the street notice me, but no one cares. Later that morning a young store assistant walks over to me. With gentle hands, she slips my arms into a white crepe shirt. The two top buttons left undone. She lowers me onto the worn carpet to get a pair of tights on me. This is something she hasn’t got the knack of. It takes her a long while to get them on; she has to wiggle my feet about to get them over my heels. It gives me a chance to look around the store. The other models are poorly made, and some are downright grotesque — missing limbs and decapitated bodies. I try not to judge, but some of the clothes they wear — good heavens! None of their outfits matches. Once I am back upright, she pulls a knee-length blue pencil skirt around my waist. The look is complete with a matching blazer. A business suit! I feel power and authority hum through my plastic body. The young woman repositions my arms before leaving. I now stand with authority, arms folded across my chest—the ruthless stance of the modern business age.

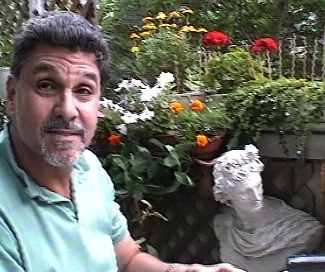

He says he wants to be my boyfriend. He tells me he loves me. Maybe he does. In the evenings I usually see him. He once told me this is his favourite moment of the day. I want to be a good girlfriend, so it is my favourite moment of the day also. When he first came into the store, he was nervous. It was only a couple of days into the new year. On a meandering journey towards my window, he stopped several times. He pretended to look at clothes on a rack or to look at his watch. When he stood by my side, he introduced himself, almost in a whisper. He often glanced around the store and touched his face when he spoke. He told me he felt the need to explain his actions from New Year’s Eve. He said it had been six months since he last spoke to Maria, his ex-girlfriend; we don’t like her or her new boyfriend, Kenny. He tells me they had been through difficult times before and assumed they would get through this one. They had a fantastic social life, both together and separately. Then one night, she left without warning. She phoned him two days later to explain that she’d met someone else. My boyfriend imagined Maria and her new boyfriend celebrating New Year’s Eve together. Maybe on some exotic beach — drinking fluorescent cocktails and giggling under a warm sun. He said that night in his apartment; he could hear their laughter echoing around his head. He said he would never have gone through with jumping. He tells me he is dependable.

summer

The endless days and humid nights can mean only one thing: summer has finally arrived. It warms the street, igniting the weeds and grasses that grow in the cracked pavement.

Customers now fill the store daily. They rush about, caught up in the heat and frenzy of the long days. Gone is my business attire. The young assistant has given me a beautiful cotton dress and matching sandals. My legs feel the warmth of the morning sun shining through the store window. I also have a new posture! It’s the pose of someone who should be carefree and ready to embrace the world — a hand on my hips, one arm flying in the air and a twist in my waist. The dress and happy-go-lucky demeanour do have their downsides; the men on the street leer at my breasts and hips and partially exposed legs as they walk past the window. My boyfriend never leers. When he tells me he loves me, I can see happiness on his face. There is no reply. My lips do not move. My face remains static. None of this matters. For the first time, he visits me during the workday. He should be in the office, but he is ill. He suffers from hay fever and has taken two days off. He comments on my new dress; he likes my new look. My boyfriend has more confidence now. He no longer appears awkward. He stands up straight. One day he says, ‘I got you this.’ He puts a thin silver bracelet on my wrist and beams. When he leaves, I hear the women from the department store snigger. They call my boyfriend a ‘weirdo’ and an ‘oddball.’ He sometimes talks about all the little things Maria said that upset him. He has a long list. I think this is why I appeal to him. Outside, people’s responses are unpredictable, frightening or demeaning in his world. Wrong reactions seem to upset my boyfriend. I give him a predictable comfort; I have never said an unkind word to him. I cannot offend him by being aloof or giving him an upsetting look. Our relationship is sterile but clean and free from the usual strains.

autumn

The nights grow darker, with the last of the summer fruits eaten. Leaves lay glossy on the rain-washed street.

I have a seductive bedroom look, a sensual bodysuit with a strappy open front and keyhole crisscross-lacing back. It’s made to thrill, complete with a bold red robe. My hand has been placed across the top of my chest, with the other resting by my side. It is a beautiful pose to bring out my desirability and femininity.

My boyfriend is taken aback the first time he sees my new look. He is nervous, like the first time we met in the store. After a few more visits, he gains confidence. When no one in the store is looking, he tenderly strokes my leg. Sometimes he holds my hand as he tells me about his day. His palms are always sweaty. He is thoughtful. He always asks me questions like, ‘Are you warm enough?’ He never looks at others as he walks over. His passionate eyes are permanently fixed on mine. Does it matter if I’m not real? It doesn’t matter to my boyfriend. When a man stares at a naked woman, is it her personality he is interested in? Is a woman’s personality not something that some men wish to escape from? One time his phone rang while we were together. He pulled it out and scoffed at it. ‘Now she calls when I’m finally happy again.’ He hangs up and replaces the phone into his jacket. I heard today he might be going to Hong Kong next month for a business trip. ‘It’s up in the air right now, but if it does happen, I’ll bring you back something nice.’ His gaze goes down my body before he looks back up at me and caresses my cheek. ‘It’ll only be for a week… Absolutely not, work only. I have no intention of visiting those places.’

winter

The bitter wind outside reminds us that winter is approaching fast. I observe frost glistening on the pavement in the morning half-light. Within the apartment block across the road are every child’s Christmas dreams.

A new store assistant dresses me. She is middle-aged and has a large face with plump lips and a thick mask of makeup. She handles me firmly but not with malice. She turns around as she removes my lingerie. I inspect the other models — they’ve not had a good year. Most have cracks in their skin, and all have scraggly hair. When the assistant is finished, I am back, staring out the window. I’m wearing a beautiful vintage-inspired mint-green winter coat, a perfect antidote to any winter blues. Made from luxurious, soft materials with a detachable hood and faux fur trim, she has even teamed my outfit with a pair of matching gloves and a cosy knitted scarf.

Snow begins to fall. I watch as cascading flakes dance on the wind. My boyfriend is walking down the street; plumes of his breath rise into the slate-grey sky. I see him approaching behind me in the reflection of the store window. We look like a washed-out photograph. When he does turn to face me, he still has snowflakes in his hair. He tells me he likes my new coat and says I look ‘homely’. Then he explains that he turned down his business trip because he couldn’t be away from me. The way my boyfriend looks tells me I should be happy, so I am happy. He reminds me it’s been almost a year since we first met. He tells me he has a particular question to ask me tomorrow. My boyfriend looks excited.

When the store is closed at night, a middle-aged store assistant talks to some men; I hear them say I will be relocated to a new flagship store in a big city. I take a last look across at my boyfriend’s apartment. I guess I am also capable of betrayal. I wonder what he wanted to ask me tomorrow. I’m escorted to a van. As I am driven away into the winter night, I guess we’ll see how much he really does love me, as he said he does.

Thomas Paul Smith is a writer from London, England. He works as a radio show producer in Dubai.